Control Premiums – Do Software Investors Pay Premiums for Control?

Overview

The M&A and capital raising market is responsible for trillions of dollars’ worth of transactions globally every single year. The key drivers come from business founders or shareholders that are looking for liquidity or capital to drive growth. Whether it be to take some “chips of the table” and continue operating the business day-to-day, exit the business completely to start a new venture or retire, or raise money to drive growth (i.e. built out a sales team, hire developers to launch a new product, etc.), there are many different kinds of transactions founders can pursue with strategic or institutional investors to achieve these objectives.

In this blog, we take a look at two different types of transactions in the software space – (1) minority transactions, such as venture capital (VC) funding or private equity (PE) growth capital funding, and (2) majority PE or strategic transactions (i.e. where a > 50% stake is purchased) – and then evaluate what the valuation implications are for each of these types of transactions. Furthermore, we also go over what control premiums are, whether they hold true in the software space, and if not, why not.

What is a Control Premium?

A control premium, simply put, is a premium above the market price a buyer is sometimes willing to pay in order to acquire a majority stake (i.e. > 50%) of a target business. Having a majority stake in a target business has many important implications – it gives the buyer (1) full control over strategic and operational decisions, (2) the ability to overturn decisions made by minority shareholders it disagrees with, and (3) the ability to much more easily increase its stake in the business or exit the business when it desires, among others.

A 2019 study conducted by the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) found that the average control premium paid by buyers in public company acquisitions to be 31.2% in the first half of 2019, and 30.2% on average since 1990. While it makes sense for a control premium to hold true in public company acquisitions, which typically require a premium to be paid to the current share price in order to get Board and Shareholder approval, we will now look at whether this holds true for minority and majority VC, PE, and strategic transactions in the software space.

Minority and Majority Transaction Valuations in the Software Space

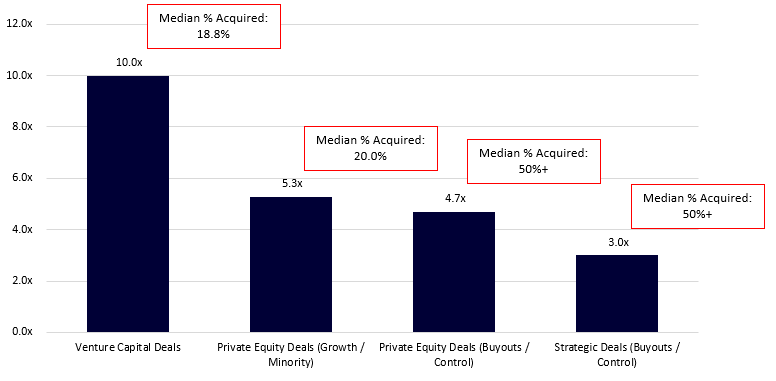

In order to look at minority and majority VC, PE, and strategic transactions in the software space, we looked at transaction data from Pitchbook dating back to 2016 in both the US and Canada and evaluated the median revenue multiples of such transactions. A brief summary can be seen below:

Source: Pitchbook.

As you can see, VC funds invest at the highest valuations (median of 10.0x revenue), followed by PE funds doing growth capital / minority transactions (median of 5.3x revenue), followed by PE funds doing buyout / control transactions (median of 4.7x revenue), and then followed by strategics doing buyout / control transactions (median of 3.0x revenue). Based on this data set from Pitchbook, the concept of control premium does not necessarily hold, and we evaluate some possible reasons and also potential limitations to help explain this.

Why the Control Premium Does Not Hold True

There are a few reasons why we believe control premiums do not hold true in the data set analyzed:

Minority investors, like VC funds and growth equity / minority focused PE funds are investing in more growth oriented businesses, which naturally warrant higher valuations because of those growth expectations. Majority / buyout investors are often investing mature and slower growth businesses which warrant lower valuations because of the limited growth potential.

VC investors typically take a different approach to PE and strategics – with a significant portion of their portfolio “failing” while PE and strategics want every deal to succeed. Therefore, VC investors take much more risk and success hinges on whether growth metrics are met.

Founders who feel they are “really on to something good” typically have lots of VCs competing for their attention and generally will not accept a term sheet unless it is significantly in their favor from a valuation and % acquired standpoint.

Minority deals often place significant importance on the founder or existing management team staying in place to drive growth, which can require a premium.

Past studies on control premiums focus on public companies, which typically require a premium to be paid to get Board and Shareholder approval, while minority investments in public companies can just be made at the current trading valuation.

VCs typically won’t let founders participate in the round by selling their shares – i.e. the money has to go into the company rather than the founders cashing out. This aligns the risk between the VC and the founders. PE and strategics on the other hand are typically buying founders out of their stake and transferring the risk.

While this shows control premiums don’t typically exist in software deals and VCs are investing at higher multiples than control investors, there are obviously exceptions. It will also be interesting to see if VC risk appetite shifts given recent events and these entry multiples come down as a result of that de-risking strategy.

Written by Sampford’s Boris Petkovic.

About Sampford Advisors

Sampford Advisors is a boutique investment bank exclusively focused on mid-market mergers and acquisitions (M&A) for technology, media and telecom (TMT) companies. We have offices in Toronto, Ottawa and Austin and have done more Canadian mid-market tech M&A transactions than any other adviser.